Third Review of Amendments to the National Defence Act Pursuant to Section 273.601 of that Act: Military Police Complaints Commission Submissions to the Independent Review Authority

Date: January 7, 2021

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION

- OUR SUBMISSIONS

- EXPANDED ACCESS TO INFORMATION

- Introduction

- Documentary Disclosure Requirements

- Access to Witnesses: Expanded Subpoena Power

- Access to Sensitive Information

- Access to Solicitor-Client Privileged Information

- Easing Certain Evidentiary Restrictions for Public Interest Hearings

- Addition of the MPCC to Privacy Regulations Schedule II

- MORE FAIR AND EFFICIENT PROCEDURES

- Introduction

- Authority to Identify and Classify Complaints

- Right of Review for Conduct Complaint Subjects

- Extend Complaints Process to All Persons Posted to Military Police Positions

- Expand Availability of Informal Resolution

- Time Limits for Requesting a Review and for Providing the Notice of Action

- Chair-Initiated Complaints

- Additional Discretionary Authorities for Disposing of Complaints

- Extension of Members’ Terms Where Cases Ongoing

- Expanding Scope of Interference Complaints

- CFPM to Report back to MPCC on Implementation of Recommendations

- Legislative Consultation with MPCC

- MILITARY POLICE INDEPENDENCE

- LIST OF PROPOSALS

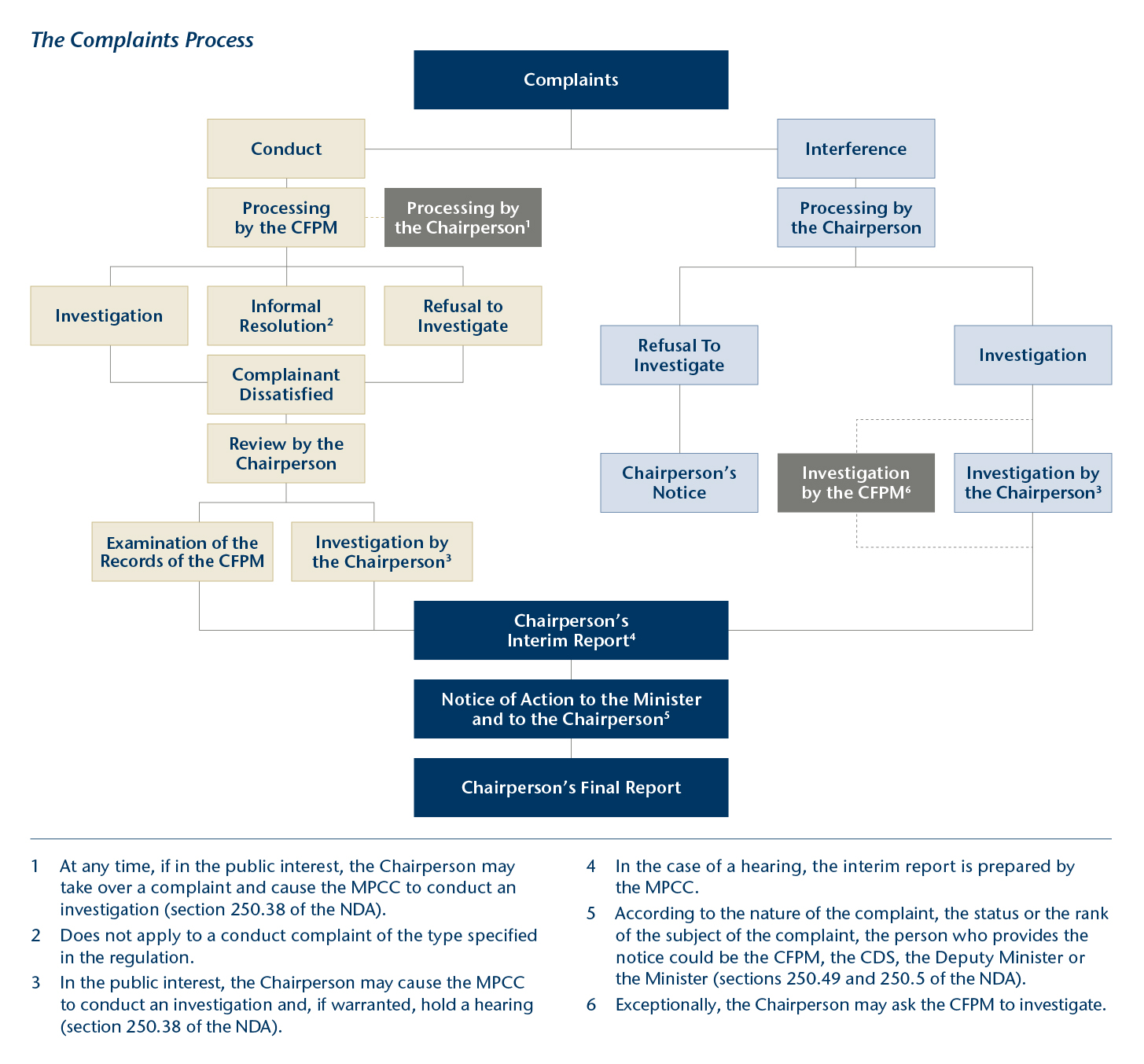

- ANNEX A – THE COMPLAINTS PROCESS CHART

- ANNEX B – GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TO PETITION

- ANNEX C – MPCC SUBMISSIONS IN RELATION TO BILL C‑15

PREFACE

The Military Police Complaints Commission (Commission or MPCC) is pleased to have the opportunity to participate in the third National Defence Act (NDA) review, now conducted under the authority of section 273.601 of that Act. As a creation of the 1998 National Defence Act amendments (S.C. 1998, c. 35) originally contained in Bill C-25 of the 1st Session of the 36th Parliament of Canada, the MPCC is an important stakeholder with direct experience in the functioning of the legislation, specifically in respect of the military policing complaints regime created in Part IV of the Act. The background to the creation of the Commission, as well as its current method of operation, can be found in the companion Foundational Briefing document.

During the past two decades, the public’s conception of law enforcement, and its appreciation of the need for robust oversight regimes, have evolved considerably. Often, such change has been precipitated by public inquiries into specific, controversial events – such as, British Columbia’s 2008‑10 Braidwood Inquiry into the tasering death of Robert Dziekanski at Vancouver International Airport; and the 2004-06 federal inquiry, let by Justice O’Connor, into the role of RCMP national security officials in the rendition of Maher Arar by the US to Syria, and his mistreatment and torture there at the hands of Syrian authorities (Arar Inquiry). More recently, there have been significant social and political responses to controversial police use of force episodes, especially in the United States – but also, and increasingly, due to events here at home. The Black Lives Matter movement is perhaps the most prominent example.

The legislative regime for complaints concerning the Military Police (MP) contained in Part IV of the National Defence Act is based in large measure on the regime for public complaints against members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) set out in Parts VI and VII of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act (RCMP Act). However, in 2013, subsequent to the last Independent NDA Review, the Enhancing Royal Canadian Mounted Police Accountability Act significantly overhauled the RCMP Act.Note 1 This Act represented a major part of the Government of Canada’s response to the recommendations of the Arar Inquiry.

Oversight bodies in other areas, such the Office of the federal Public Service Integrity Commissioner, established in 2007, have also been given robust authorities to discharge their mandates.

The MPCC is now more than 20 years old. In the two decades since its creation, both the provinces and the federal government have established new, or significantly revised, independent police oversight bodies. These newer bodies have invariably surpassed the MPCC in the strength of their oversight authorities. As reforms and changes in oversight continue, the MPCC falls further behind, and its relatively modest legal authorities become increasingly outmoded.

INTRODUCTION

Particular Challenges of the MP Complaint Process

The process for dealing with MP conduct complaints is a mixed, internal/external one. The CFPM has the initial responsibility for dealing with a complaint. If a complainant is dissatisfied with the result of a CFPM’s Professional Standards investigation, they can ask for a review by the Commission, a civilian review agency with no police or military affiliations, save that it reports to Parliament through the Minister of National Defence. The Commission’s review may go beyond looking at the adequacy of the internal police investigation and conduct an investigation de novo. Upon receipt of the Commission’s Interim Report, the only statutory obligation imposed on Military Police authorities is that they must respond to its findings and recommendations and provide reasons for not acting on recommendations should they decide not to follow them.

This shared, internal-external model of oversight was recommended by former Chief Justice Brian Dickson in 1997, who following the Somalia Inquiry led a special advisory group constituted to review the identified issues and recommend reforms for the military justice system. In part the report stated:

“The current trend in police forces around the world has been to adopt an oversight process that combines an internal and external review mechanism. In order for a police chief to be held accountable, he must be given the initial opportunity to resolve the dispute internally. This allows him to control the priority of investigative resources, in addition to providing critical expertise in the form of internal investigators who have inside knowledge of the police organization. It is paramount that the police force be able to enforce internal discipline by demonstrating to its members and the public that misconduct will not be tolerated. An independent review capability is equally essential to ensure confidence and respect for the military justice system.”

This model also recognizes that, unlike civilian police services, the Military Police is a police service within a larger hierarchical organization, the Canadian Armed Forces. This means that the oversight regime needs to take into account the fact that, as part of a military force, the Military Police chain of command is expected to assume responsibility for matters of performance and discipline to a greater extent than their civilian police counterparts. This includes being subject to a separate internal penal system in the form of the Code of Service Discipline (in NDA Part III), which can impose true penal consequences on all military members. Additionally, the CFPM is charged with enforcing the Military Police Professional Code of Conduct, and it is he or she who controls who retains their Military Police credentials. In this military context, it would be anomalous for a civilian agency to direct and discipline MPs in the performance of their duties.

The situation is similar to the RCMP and the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP (CRCC). A complaint about a member of the RCMP is first dealt with by the RCMP itself. If a complainant is dissatisfied with the resolution of their complaint, they may bring it to the CRCC for review. The RCMP has traditionally considered itself to be a para-military organization, with a command structure similar to that of the military. It too had its own internal penal code which used to impose true penal consequences.Note 2 Only recently, has the RCMP been allowed to unionize, like their provincial and municipal counterparts. Historically, one of the RCMP’s roles was as a reserve police service in the event of a strike by local police. So for reasons similar to the Military Police, the RCMP complaint system likewise follows a two-stage approach, with complaints initially being handled in-house and only later being sent to an outside civilian agency that provides recommendations only.

This dual, internal/external complaints process under Part IV does, however, have its challenges.

The question of jurisdiction is ever-present: at the complaint-intake stage; the planning and conduct of any investigation; and the drafting of our reports. No other police oversight body faces this challenge of having only certain of the duties of its overseen police members subject to the complaints process and external oversight. This said, after twenty years, the MPCC and the CFPM have managed to chart many of the grey areas of the jurisdictional divide. Dialogue, and some disagreement, do continue however. For this reason, the MPCC is proposing it be given the task of determining (subject to the supervisory jurisdiction of the Federal Court) whether or not the MP complaints regime in NDA Part IV applies in a matter or not (see below, Proposal #7).

Another special feature of the MPCC’s work is that, unlike local and provincial police oversight bodies, the scope of the MPCC’s work is national and, indeed global. Moreover, being military members, MP subjects, and many of our complainants, are frequently redeployed to different locales. This inevitably affects the logistical complexity of conducting complaint investigations.

On paper, the MPCC, for the purposes of conduct complaints, is largely meant to be a body of review. However, in reality, the MPCC’s role in resolving conduct complaints has been much more dynamic and intensive.

Some files are significantly more complex and voluminous than others, yet they are all counted the same for statistical purposes. Our public interest hearings, though few in number, have often been as resource-intensive as a public inquiry. For instance:

- MPCC 2008‑042 (Amnesty International Canada & BC Civil Liberties Association) Public Interest Hearing - A public interest hearing into a third party complaint against members of the CFNIS and the CFPM for failing to investigate Canadian Task Force Commanders for their decisions to transfer Afghan detainees to the custody of Afghan security forces knowing that there was a significant risk of torture or other abuse at the hands of those security forces. As noted elsewhere, this case was subject to significant delays due to the MPCC not being on the Schedule to the Canada Evidence Act, and the unwillingness of the Attorney General to proceed with a disclosure agreement for sensitive information pursuant to section 38.031 of that Act. In all, the MPCC estimates a delay of some 20 months in receiving documents pursuant to its summonses issued under NDA subsection 250.41(1). The public interest hearing was the subject of an unsuccessful judicial review application by certain of the subjects of the complaint.Note 3 Ultimately, the hearings proceeded with 40 witnesses heard over 47 days of hearings and dealt with numerous motions. The witnesses included those providing background information on the structure of the CAF and the Military Police, as well as a panel of experts in international law. Witnesses were also called to address apparent gaps and problems in document production. This case involved the review of thousands of pages of documents. In all, the file took four years to complete which was of great concern to the Commission. The complaint was dated June 12, 2008 and substantive hearings began on April 6, 2010 (prior to that some background and contextual evidence was called and preliminary motions were heard) following which the Final Report was issued on June 27, 2012.

- MPCC 2011-004 (Fynes) Public Interest Hearing - This case was the result of a complaint by the family of a deceased CAF member who had committed suicide at CFB Edmonton in 2008. The complaint challenged the professionalism and objectivity of various MP investigations into the soldier’s suicide, and the potential responsibility of his unit chain of command for not adequately responding to the soldier’s mental health needs, as well as the handling of matters relating to his estate. This case involved the review of some 22,000 documents and the testimony of 90 witnesses over the course of 62 hearing days. The MPCC made 96 recommendations in this case.

Moreover, some of our public interest investigations, and even ordinary conduct complaint reviews, have approached this level. A few examples will illustrate the point.

- MPCC 2007‑003 (Attaran) Public Interest Investigation - This was a public interest investigation into a third-party complaint alleging that Afghan detainees were injured while in CAF custody in Afghanistan. This investigation involved the review of some 5,500 pages of documentation and the interviewing of 35 witnesses. This case also saw the establishment, at the instance of our then Chairperson, Peter Tinsley, of a unique protocol between the MPCC and the CFNIS, which through coordination of witness interviews and information-sharing, allowed the MPCC to commence its complaint investigation while the CFNIS criminal investigation into the underlying events was ongoing. It is most unusual for an administrative investigation such as ours to proceed in tandem with a police investigation. This enabled us to complete our investigation considerably sooner than would normally have been the case. The protocol in this case is an example of the MPCC’s creativity in, and inclination towards, finding a way forward when confronted with potential obstacles.

- MPCC 2008‑018 Public Interest Investigation - This complaint related to the treatment of persons detained by MPs for mental health purposes. This public interest investigation involved the interview of around 25 witnesses. But this case is also an example of where the MPCC’s investigation included a “best practices” review. This involved the MPCC surveying the policies and practices of various other police services with regard to their policies and practices in dealing with mental health detainees. This enabled us to see how Military Police policies compared with those of other police services and to make better informed recommendations. Such best practices reviews are frequently part of our complaint reviews and investigations, as we seek to extract as much benefit from each case as we can.

- MPCC 2015‑005 (Anonymous) Public Interest Investigation - This is an ongoing public interest investigation into a complaint about the alleged abuse of detainees by MPs in Afghanistan in 2011. This investigation has involved 71 interviews and the review and analysis of over 3000 pages of documentation. It also required considerable effort to negotiate the inspection of hundreds of boxes of deployment-related records held at Canadian Joint Operations Command Headquarters which resulted in several weeks of review by MPCC staff for relevant documents. The MPCC is currently nearing completion of its Interim Report.

- MPCC 2016‑040 (Beamish) Public Interest Investigation - This case concerns the CFNIS investigation of historical allegations of abuse of CAF trainees in 1984. The alleged mistreatment was intense and apparently fell outside the applicable training standards. A number of participants, including the complainant, claim the experience caused or contributed to their PTSD. For this investigation, the MPCC conducted 35 interviews and reviewed over 3000 pages of documentation. The MPCC is presently preparing its Interim Report in this case.

- MPCC 2011‑046 Conduct Complaint Review - This case concerned the CFNIS investigation of the disappearance and death of an officer-cadet at the Royal Military College. Technically, this file was an ordinary conduct complaint review. However, the disclosure was massive, as the matter had been previously subject to a number of investigations by other agencies, including the coroner’s office, the OPP and the RCMP. Apart from conducting 39 witness interviews, the MPCC had to review some 200,000 pages of documentation (70 gigabytes of data).

Yet, unlike public inquiries, we cannot dedicate all our resources to any single large and complex case. We must continue to address all the other complaint files that are open at any given time (not to mention the non-stop corporate reporting to central agencies, which is the necessary price of our independence from DND).

Finally, the sufficiency of the first-stage complaint disposition by the CFPM’s office of Professional Standards has also been problematic over the years. Frequently, when the MPCC receives a request for review, it becomes apparent that the Professional Standards response to that complaint has been inadequate: witnesses not interviewed; allegations overlooked; records not examined, etc. Sometimes, the Professional Standards disposition has been otherwise non-responsive to the complainant, e.g., by misconstruing the complaint, or unduly limiting the scope of responsibility for the impugned MP actions.

An extreme example occurred recently with conduct complaint file MPCC 2016‑027. This complaint arose from a CFNIS investigation into a house fire at a base housing unit. The CFNIS investigation ruled the fire accidental, and so did not pursue charges. The case was never referred to a prosecutor. The complainant filed a conduct complaint. The CFPM’s Professional Standards office determined that the CFNIS investigation was fine and dismissed the complaint. The complainant requested a review by the MPCC. After reviewing the CFNIS investigation (and the fire marshal’s report, which was not in the CFNIS investigation file disclosed to us, and did not appear to have been obtained by them in the course of their investigation), the MPCC determined that there were significant problems with the CFNIS investigation – so much so, that the MPCC felt it necessary to stop its review and send the case back to the CFPM, with a recommendation that further police investigation of the fire be undertaken. This was done, with the result that an accused is presently on trial for attempted murder and arson.

Sometimes Professional Standards’ disposition of a complaint has been non-responsive deliberately for policy reasons. Recently for example, Professional Standards has declined to address conduct allegations that are framed by the complainant as breaches of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the Charter), and even those which are capable of being so framed. Despite not being a court of competent jurisdiction under section 24 of the Charter, there is no reason why Professional Standards cannot address the appropriateness of the underlying conduct, without purporting to make a Charter ruling. This is the approach the MPCC takes. Complainant’s should not be penalized because they happen to describe MP misconduct in legal terms.

So, given the foregoing, in practice, the MPCC frequently does more than a simple ‘paper’ review. Even when the MPCC does conduct a purely paper review, these can be quite labour intensive, as was the case with MPCC 2016‑027, discussed above.

To address this problem, the MPCC is now proposing that it be given the authority to send complaints back to Professional Standards with binding directions as to further investigation required (see below, Proposal #18). If adopted and implemented, this reform would enable the MPCC to better manage its caseload and move away from so much de novo investigation of conduct complaints, and allow it to focus its investigative resources on public interest and interference cases.

Our Submissions

The general theme of the MPCC’s submissions is that the system of civilian oversight of military policing needs to be strengthened to ensure the confidence of complainants, subjects, and the public. As it stands, the system is too vulnerable to criticism on the grounds that it is insufficiently robust to provide the needed level of confidence in the professionalism, integrity, and independence of military policing.

That being said, the MPCC is not challenging the fundamental nature of its oversight mandate, which is one that is advisory, rather than adjudicative or directive. The lack of binding authority, however, needs to be balanced by a more robust oversight system with access to information that is timely and adequate for the nature of the cases it is called upon to investigate. A cooperative relationship between the Military Police leadership and the Commission is important, but a credible oversight regime should not hinge on this to the extent that the current model does.

In addition to urging better and quicker access to information, the MPCC’s submissions relate to enhancing the efficiency and fairness of the complaints process. Overall, our proposed changes are intended to bring the Commission into closer alignment with current best practices in police oversight.

The MPCC sees no reason why the legislative review process should not be an interactive one and, as such, the MPCC is pleased to receive feedback on its proposals from other National Defence Act Part IV stakeholders as well as the independent review authority, and to participate in a joint dialogue or discussion on areas of mutual concern. In past legislative reviews, a number of our proposals do not appear to have been considered or seem to have been rejected without reasons or discussion with us. For instance, in the last legislative review, when we met with Justice Lesage in respect of our June 2011 submissions, he was very much attracted to our proposal that we be given the power to classify complaints, in terms of whether or not they fell within NDA Part IV (see current proposal #7). So much so, that he requested we provide draft legislative language for implementing our proposal, which we did. However, in his report dated December 31, 2011 (but released only in June 2012), this proposal was essentially ignored, with no explanation. There were also other MPCC proposals to which Justice Lesage had seemed favourably disposed when we met with him, but which did not end up being advanced – and often not even mentioned – in his report. Apparently, something caused him to change his mind about these issues, but no concerns were raised with us, and we had no opportunity to respond to whatever difficulty or objection may have arisen. As such, the MPCC is respectfully requesting the opportunity to respond to any reservations or criticisms regarding its proposals before the review authority finalizes his report to the Minister.

Original signed by

Hilary C. McCormack

Chairperson

Military Police Complaints Commission

Ottawa, January 7, 2021

OUR SUBMISSIONS

I. EXPANDED ACCESS TO INFORMATION

A. Introduction

1. To put it plainly, the MPCC’s legal authorities to gain access to information necessary to monitor, review and investigate complaints in an effective and credible manner are inadequate, and have been for some time. Such authorities are too few in number, too narrow in scope and too dependent on the goodwill of the overseen police service leadership. More secure and expanded access to relevant information is necessary for the MPCC to provide credible and effective civilian oversight of military policing, especially in those controversial situations where external oversight is most crucial for ensuring public confidence.

2. The stakes are high. Military Police exercise important policing responsibilities in Canada and they are the only policing authority for Canadian personnel on military deployments abroad. The types of cases that Military Police can become involved with, as we know from the long and intensive mission in Afghanistan, can easily test at least the perceived integrity and professionalism of military policing, and military justice generally. This perception on the part of the larger military community and the Canadian public is vital to upholding the rule of law, and often even to the success or failure of a mission.

3. The Canadian Armed Forces Military Police call themselves ‘Canada’s Front-Line Police Service’, and so they are. They are at once soldiers and law enforcement agents, committed to the success of the chain of command’s operational missions and to upholding the rule of law. They are part of the military chain of command and yet are expected, in fact required, to use independent judgement in performing their policing duties. They need to be prepared to investigate and, in some cases arrest and charge, other military members of higher rank. Needless to say, there can at times be tensions between their duties as soldiers and as police. Reconciling these responsibilities is no doubt often an unenviable task.

4. The Military Police need and deserve an oversight body that has the capacity to independently and credibly address Military Police conduct or interference complaints, identify problems and possible solutions, and dispel unfounded allegations and suspicions.

5. There are two fundamental qualities for such a police oversight body, or indeed, any credible “watchdog”-type body: 1) operational independence from the overseen organization; and 2) clear, legislative authority to command access to relevant information from the overseen entity.

6. It is in the area of authoritative access to information where the MPCC believes there to be considerable need for improvements. Toward that end, the MPCC has developed some specific proposals to enhance its access to information. There are already established precedents for many of these legislative authorities in the area of federal police oversight, specifically in the powers conferred on the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP (RCMP Commission) in the 2013 amendments to the RCMP Act following the recommendations of the Arar Inquiry.

7. The MPCC does not have the power to enforce its will on the Military Police leadership. It makes only non-binding findings and recommendations. Nor does the MPCC seek such authority. Strong authorities for the MPCC to access information could be considered an appropriate trade-off for the lack of authority to intrude on military chain of command relationships.

B. Documentary Disclosure Requirements

8. Presently, the only instances where the MPCC has a statutory right to obtain information in support of its investigative and oversight responsibilities are when a review of a conduct complaint is requested (National Defence Act, s. 250.31(2)(b)), or when it exercises its subpoena power in the context of a public interest hearing (National Defence Act, s. 250.41). There is no statutory right to information in respect of an interference complaint or a public interest investigation, a significant anomaly. Nor is there a statutory right to access documents in the possession of the broader Canadian Armed Forces or the Department of National Defence. The MPCC has had to rely on the goodwill of Military Police Professional Standards for disclosure in interference complaints and public interest investigations. This is unacceptable for an independent, statutory oversight body. As the Federal Court has stated regarding the MPCC: “If the Commission does not have full access to relevant documents, which are the lifeblood of an inquiry, there cannot be a full and independent investigation.”Note 4

9. Furthermore, the courts have indicated that it is not an appropriate use of a discretionary public-hearing power merely to secure cooperation in the disclosure of relevant information.Note 5

10. It would also help the MPCC to better discharge its mandate by allowing it to have access to Military Police records at various stages of the complaints process (Annex A ‑ Complaints Process Chart), as does the RCMP Commission.Note 6 Access to records at the earlier, monitoring stage of the conduct complaints process (i.e., when a complaint is first received, or is being dealt with by the office of Military Police Professional Standards) would better enable the MPCC to monitor the internal Military Police treatment of complaints. It would also allow the MPCC to make more timely and better informed decisions on the exercise of its public interest authority to take over the handling of a complaint from the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal (CFPM), which the Chairperson is authorized pursuant to subsection 250.38(1) of the National Defence Act to do “at any time”. More timely and informed decisions for the MPCC to intervene in the public interest would save time and duplication of effort, as between the MPCC and the CFPM.

11. The timely access to information relevant to a complaint would also help the Commission fulfill its duty to deal with all matters before it as informally and expeditiously as the circumstances and the considerations of fairness permit.Note 7 An early resolution of a complaint can be considered part of “a general right to procedural fairness, autonomous of the operation of any statute.”Note 8 In the case of matters before the Commission, an inordinate delay is unfair to a complainant who wants to see the results of an impartial review as soon as possible as well as to the subject Military Police member who is exposed to a degree of risk to his or her reputation, as well to deployment and career opportunities, while a complaint looms over them.

12. MPCC access to Military Police records after the conclusion of the complaints process would allow the MPCC to monitor the CFPM’s implementation of reforms promised in the Notice of Action under section 250.51 of the National Defence Act. Such knowledge would assist the MPCC in making helpful recommendations in subsequent cases.

13. The MPCC considers that the authority given to the RCMP Commission in subsection 45.39(1) of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act offers a good model for the type of provision that the MPCC is proposing. It states that the RCMP Commission is entitled to “any information under the control, or in the possession, of the Force that the Commission considers is relevant to the exercise of the Commission’s powers, or the performance of the Commission’s duties under this Act.”

14. A notable feature of this provision is that it stipulates that it is the oversight body’s view of the relevance of the information which is decisive. In the case of the MPCC, the Federal Court has already stipulated that it should be the MPCC’s perceptions of relevance which guide the fulfillment of disclosure requirements to the MPCC.Note 9 Nonetheless, it would be useful to have this principle set out in the legislation in order to preclude time-consuming, and continuing, arguments about relevance with the CFPM, the Canadian Armed Forces, and the Department of National Defence, which only serve to undermine the credibility of the oversight process.

1) The MPCC proposes that Part IV of the National Defence Act be amended to require the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal, the Canadian Armed Forces, and the Department of National Defence to disclose to the MPCC all records under their control which, in the view of the MPCC, may be relevant to the performance of its mandate.

C. Access to Witnesses: Expanded Subpoena Power

15. In addition to its inability to compel access to documentary evidence, the MPCC has an extremely limited power to compel witnesses to provide testimony. Aside from being able to issue a summons to witnesses when conducting a public interest hearing,Note 10 the MPCC has no legal authority to oblige witnesses to give evidence. It is reliant upon the good-will of those with knowledge concerning complaints to cooperate voluntarily. The Commission’s lack of authority to compel witnesses cannot be justified in the name of protecting witnesses from potentially adverse legal consequences of their testimony as the Commission is an administrative, not a disciplinary body. As with access to Military Police records, the MPCC’s discretionary public interest hearing powers, and the associated increases in the formality and cost of proceedings, should not be engaged solely to gain access to compelled cooperation.Note 11 After all, the MPCC is under a statutory direction to conduct its business as informally and expeditiously as possible, consistent with fairness.Note 12

16. Canada’s other federal police oversight body, the RCMP Commission, has been given the authority to summons witnesses in dealing with any complaint before it in any of its processes, not just its hearings.Note 13 The Military Grievances External Review Committee also has a power to issue witness summonses. The Grievance Committee has, in relation to the review of a grievance referred to it, the power “to summon and enforce the attendance of witnesses and compel them to give oral or written evidence on oath and to produce any documents and things under their control that it considers necessary to the full investigation and consideration of matters before it.”Note 14 A further example is that, in conducting an investigation, the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner has all the powers of a commissioner under Part II of the Inquiries Act.Note 15

17. The legal ability to compel testimony would put the Commission into a similar position as the Provost Marshal. Under the Military Police Professional Code of Conduct there is a duty imposed on members of the Military Police to cooperate with Provost Marshal investigations. Under section 8 of the Code, no member of the Military Police is excused from responding to any question relating to an investigation into a breach of the Code unless the member is the subject of the investigation or is the assisting officer for the subject of the investigation. Another duty to cooperate is found in Defence Administrative Order and Directive 5047‑1, Office of the Ombudsman. Annex A of that DAOD contains a Ministerial Directive that imposes a duty on all Canadian Armed Forces and Department of National Defence personnel to cooperate with investigations by the National Defence and Canadian Forces Ombudsman. Refusal or failure to assist the Ombudsman can result in the Ombudsman making a report of the matter to the Minister of National Defence.

18. With compelled testimony comes legal protections. One example is subsection 45.65(3) of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act which states that evidence given, or a document or thing produced, by a witness who is compelled by the Commission to give or produce it, may only be used against the witness in perjury proceedings.Note 16 As it stands, witnesses who volunteer to provide evidence to the Commission are at risk of having that evidence used against them in other proceedings.

2) The MPCC proposes that Part IV of the National Defence Act be amended to give it the power to summon and enforce the attendance of witnesses before it and compel them to give oral or written evidence on oath and to produce any documents and things that the MPCC considers relevant for the full investigation, hearing and consideration of a complaint.

D. Access to Sensitive Information

19. Due to the policing mandate of MPs, the MPCC has, in the course of its work, encountered the need to gain access to what is called sensitive informationNote 17 or potentially injurious information.Note 18 Parliament in 1998 expected that the MPCC should have access to sensitive information when relevant to its mandate. Paragraph 250.42(a) of the National Defence Act provides that the MPCC may exceptionally hold its public interest hearings in camera if it expects to receive information that “could reasonably be expected to be injurious to the defence of Canada or any state allied or associated with Canada or the detection, prevention or suppression of subversive or hostile activities.” The Commission has both secure facilities and security-cleared personnel to deal with sensitive information.

20. In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001, Parliament adopted sections 38 through 38.16 of the Canada Evidence Act (CEA) to provide for a special regime of controlling access to this kind of information which may be “potentially injurious” to “international relations or to national defence or security.” Every participant in a proceeding is required to notify the Attorney General of Canada of the possibility of the disclosure of information that they believe is sensitive information or potentially injurious information. Such information shall not be disclosed, but the Attorney General may, at any time and subject to any conditions that he or she considers appropriate, authorize the disclosure of all or part of the information.Note 19 While a party or tribunal seeking access to such information for use in proceedings can challenge the Attorney General of Canada’s claim that the information in question is injurious to interests like national security, this requires that the proceedings be delayed while the issue is litigated through the courts.

21. Alternatively, a body may be added to a Schedule of Designated Entities to the CEA, as provided for in paragraph 38.01(6)(d) and subsection 38.01(8). In these cases, the disclosure restrictions do not apply and the body can receive the sensitive information in question. The idea of access to sensitive information by certain bodies was addressed by Justice O’Connor in the Arar Inquiry. In his recommendations for an RCMP oversight body, Justice O’Connor recommended that the oversight body “must have access to all relevant information and should not be refused information on the basis that it is secret or sensitive.”Note 20 The concomitant obligation for investigative bodies receiving sensitive information was to put in place stringent non-disclosure requirements. Oversight bodies that do have full access to all information include the Security Intelligence Review Committee and the Communications Security Establishment Commissioner. According to the information provided to Justice O’Connor, neither of those review bodies has breached security obligations.

22. Thus, the MPCC’s ‘sister’ oversight body in the area of federal policing, the RCMP Commission, was added to the CEA Schedule as a Designated Entity in 2013 as a result of recommendations in the Arar Inquiry. Other designated entities include the Privacy Commissioner, the Information Commissioner and the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner.Note 21

23. From the list of currently designated entities, it seems that a body must have a reasonable prospect that it will encounter such sensitive information and must have in place sufficient safeguards against uncontrolled public disclosure of such information. If and when a body considers it necessary to make sensitive information public, the regular safeguards kick in, and such disclosure must be negotiated or litigated with the Attorney General of Canada.

24. In effect, therefore, being a designated entity for the purposes of the CEA Schedule does not remove, so much as defer, the special disclosure protections applicable to such sensitive information. Yet the effect of this change would be immensely beneficial in terms of the efficiency of the proceedings in question. For one thing, being on the CEA Schedule would significantly narrow, and possibly eliminate, the scope of information whose public disclosure would need to be negotiated or litigated. This is because, having access to the information up front, the MPCC would, over the course of its investigation, inevitably acquire a more refined understanding as to what records are truly relevant to the resolution of the complaint before it. In some cases, it may turn out to be unnecessary to refer to sensitive information in its report. In those cases, being on the CEA Schedule would obviate the need for Federal Court litigation altogether. In other cases, the MPCC could issue a provisional Final Report on a complaint with some information redacted pending the results of litigation in the Federal Court.

25. MPCC access to sensitive or potentially injurious information is not an academic or speculative concern. These provisions were invoked in the MPCC’s public interest hearing related to the treatment of Afghan detainees (MPCC 2008‑042). In that case, protracted negotiations with the government and litigation were necessary to obtain access to documents. The government took the position that the MPCC could only receive documents after they were vetted and redacted. In practice, this resulted in significant delays of many months for the MPCC in obtaining documents required for the conduct of its hearings. For instance, there was a period of twenty months, between March 2008 and November 2009 where the MPCC received no documents. Moreover, in 2010, then-Chairperson Stannard was forced to adjourn the hearing for a few weeks because of further problems with document production. The Government declined Commission offers to assist in identifying records of potential relevance, and thus expedite the vetting process. The MPCC was also obliged to call witnesses and spend valuable hearing time dealing with document production and vetting issues. Indeed, it can fairly be said that disputes and delays over document production hijacked the hearing process to a significant extent. All of which made it significantly more difficult and time-consuming for the Commission to carry out its mandate. This could have been substantially avoided by having the MPCC on the Canada Evidence Act Schedule.

26. Nor were these problems with production of potentially sensitive documents confined to the especially politically sensitive Afghan detainee public interest hearing. More recently, in the current Anonymous Public Interest Investigation (based on an anonymous complaint about an allegedly illegal training exercise conducted by MPs in the Detainee Transfer Facility in Afghanistan in 2011), the MPCC confronted a delay of nine months before receiving disclosure from the CFPM. Much like justice, the delay of necessary oversight can be the denial of oversight.

27. Moreover, given the policing jurisdiction of the Canadian Armed Forces Military Police, it is only too easy to think of other scenarios where sensitive international relations or military information would be involved. For instance, it seems highly likely that a Military Police investigation into the operational conduct of members of the Canadian Armed Force’s special forces units would involve sensitive information. Indeed, the Canadian Forces National Investigation Service did investigate the conduct of members of JTF2 in respect of operations in Afghanistan.Note 22 The MPCC received no complaints about these investigations. If it had, it is difficult to see how the MPCC could have dealt with such complaints without access to this type of information.

28. At the conclusion of the Afghanistan Public Interest Hearing from a complaint by Amnesty International/BC Civil Liberties Association, the MPCC recommended that it be added to the Canada Evidence Act Schedule, both in its December 2011 Interim Report and in its June 2012 Final Report (MPCC 2008‑042). This recommendation was rejected. However, the MPCC has persisted in its efforts to advance this issue. The present Chairperson included a recommendation in the MPCC Annual Report for 2015 to have the Commission added to the CEA Schedule. This recommendation has been reiterated in subsequent Annual Reports.

29. There have also been petitions to Parliament from individuals (one law professor and one Member of Parliament) seeking the CEA scheduling of the MPCC. The Minister of Justice and Attorney General in response to one of these petitions to have the MPCC added to the CEA schedule, stated that the impediment to adding the MPCC to this list was that:

“While the mandate of the MPCC allows it to conduct in camera (i.e., closed) proceedings if information identified in section 250.42 of the National Defence Act is likely to be disclosed, the scope of section 250.42 does not fully encompass “sensitive information” or “potentially injurious information.”…Note 23

30. The solution is a two-step process: (1) Amend s. 250.42 of the NDA to encompass fully “sensitive information” and “potentially injurious information”. This would be in keeping with Parliament’s intention when the MPCC was created in 1998. (2) Add the MPCC to the CEA schedule. (Annex B ‑ Government Response to Petition). It is within the Government’s authority, rather than the Commission’s, to provide the necessary legislative authorities, particularly related to the conduct of hearings, which would enable the Commission to be safely added to the Schedule. This is indeed what the Government and Parliament did with the RCMP Commission in the 2013 amendments to the RCMP Act.

31. In his 2011 report, the Second Independent Review Authority, former Justice Lesage, declined to support the MPCC’s proposal to be added to the CEA Schedule. He did so based on the sensitivity and complexity of the issue, and his not having the benefit of more extensive submissions on the matter.Note 24 However, it must be noted that Justice Lesage’s report was submitted prior to the issuance of the MPCC’s Final Report in the Afghanistan Public Interest Hearing, and its related recommendation regarding CEA scheduling, as well as the petitions to Parliament, noted above. It must also be noted that the addition of the RCMP Commission to the CEA Schedule, along with the corresponding modifications to its hearing and evidence-handling procedures, through the enactment of Bill C‑42 in 2013, had not yet occurred. Thus, the public policy and legal landscape have shifted since Justice Lesage issued his report in December 2011.

3) The MPCC proposes that it be added to the Canada Evidence Act schedule by first amending s. 250.42 of the National Defence Act to fully address the hearing procedures and handling requirements necessary to receive “sensitive information” and “potentially injurious information”; and second, that it be added to the Schedule of Designated Entities pursuant to paragraph 38.01(6)(d) and subsection 38.01(8) of the Canada Evidence Act.

E. Access to Solicitor-Client Privileged Information

32. At present, the MPCC is unable to access solicitor-client privileged information from the CFPM. This is the case, even though the CFPM has access to such information in initially disposing of the complaint, a distinction in treatment which undermines the value of the right to independent review of complaints. Despite this present legal restriction, it is nonetheless the case that the legal advice sought and provided to members of the Military Police is often highly pertinent to resolving complaints.

33. The MPCC receives many complaints about actions taken, or not taken, with the benefit of legal advice from either military or civilian prosecutors: searches and seizures, arrests, and the laying (or not laying) of charges. Two prominent categories of complainants are: 1) those charged with offences who believe they should not have been charged; and 2) alleged victims who do not understand why charges were not laid against their alleged perpetrator.

34. Based on their experiences, many complainants in such cases are dubious as to the professional competence and independence of the Military Police. In the view of the MPCC, it is not possible to fully and fairly explain Military Police members’ charge-laying decisions without some knowledge of the pre-charge consultations between them and civilian or military legal advisors. While it can usually be assumed that members’ charging decisions reflect the pre-charge legal advice they received, the status quo does not permit the MPCC to confirm that a Military Police subject member provided an accurate description of the evidence to the prosecutor, or that the ensuing legal advice was properly considered.

35. Nor is it appropriate for the MPCC to simply substitute its own assessment of the grounds for a charging decision, or the exercise of prosecutorial discretion, for that of Military Police subject members. Such exercises of a member’s independent policing discretion and judgment are only properly and fairly reviewable on a standard of reasonableness, rather than correctness. While it is true that merely following legal advice does not operate as a complete defence to the consequential actions or decisions of a Military Police member, it is of critical importance in establishing the reasonableness of a member’s decision.

36. Therefore, denying the MPCC access to solicitor-client privileged information in these types of case undermines the MPCC’s ability to effectively and fairly review such complaints. At the same time, the MPCC considers that such access is unlikely to discourage Military Police members from being candid with their legal advisors or to avoid seeking legal advice altogether.

37. Beyond the challenge posed to the credibility and fairness of its complaints process by lack of access to solicitor-client privileged information, there is the further, significant burden of disputes with the CFPM as to the scope or applicability of privilege to a given situation.

38. For instance, it is well known that when, in the course of litigation, a party justifies its position on the basis of legal advice received, it is deemed, out of fairness, to waive that privilege for the purposes of that litigation. However, the position taken by the JAG legal advisors to the CFPM is that any privilege in legal advice provided to Military Police members in the course of their policing duties belongs to the Minister of National Defence, and that only the Minister’s actions can result in its loss or waiver. Under this analysis, the CFPM himself could not disclose the legal advice received by any of his MPs, even if he wished to do so. In fact, generally speaking, the manner in which the privilege is asserted in the context of the MP complaints process appears to be based more on obscuring the involvement of JAG and other legal advisors for the Crown, than on promoting MP candor when seeking legal advice.

39. Another area of dispute relates to the CFPM’s assertion of privilege over ‘Crown briefs’ – a compilation of materials reflecting the fruits of a Military Police investigation, which is forwarded to Crown counsel (or a military prosecutor) and is later disclosed to an accused person when charges are laid. The MPCC used to receive such briefs as part of its regular disclosure from the CFPM on complaint files. The brief is intended to enable a prosecutor to formulate advice for the investigating Military Police member as to whether charges should, or should not, be laid, and if so, which ones. While prosecutors may be asked for their assessment as to whether there are grounds for criminal or National Defence Act charges based on the elements of the offence(s), the Crown brief is also prepared and sent to the prosecutor in order to obtain advice on the exercise of prosecutorial or police discretion: that is to say, assuming that charges can be laid, should they be laid? The relevant factors here are whether the case presents a reasonable prospect of conviction and whether a prosecution is in the public interest. These are strictly policy questions, rather than legal advice. Where charges proceed, the Crown brief forms the basis for the disclosure provided to the accused.

40. Even apart from the ensuing prosecutorial advice on the exercise of charge-laying discretion, the Crown brief itself can be an important source of information for the MPCC. It can directly address complainants’ allegations that prosecutors’ charge-laying advice to the Military Police was the result of incomplete, inaccurate or biased information supplied by Military Police investigators. One significant example of the utility of MPCC access to Crown briefs arose in the MPCC’s first public interest hearing case, MPCC File # 2005-024. This was a complaint by the parent of a youth who was investigated for sexual assault against a fellow cadet at a cadet camp. The complaint was about the conduct of the principal CFNIS investigators. In that case, MPCC access to the Crown brief – over which the CFPM had not claimed solicitor-client privilege – enabled the MPCC to discover and report on the fact that a number of important exculpatory pieces of evidence had been omitted from the Crown brief by the CFNIS investigators. The MPCC’s Final Report in this case may be found at: https://www.mpcc-cppm.gc.ca/public-interest-investigations-and-hearings-enquetes-et-audiences-dinteret-public/final-reports-rapports-finals/hearing-audience-2005-024-final-report-rapport-final-eng.html (see Part V).

41. Parliament seems to have accepted the arguments for giving access to privileged communications for police oversight purposes, as it has already extended access to solicitor-client privileged information to a police oversight body. With Bill C-42, the RCMP Commission has been given wide powers of access to information – including solicitor-client privileged information – in order to carry out its oversight role. Moreover, these powers extend to the RCMP Commission’s original police complaints mandate – that which it shares with the MPCC – as well as its more recently acquired national security oversight and proactive review roles. Subsection 45.4(2) of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act states: “Despite any privilege that exists and may be claimed, the Commission is entitled to have access to privileged information under the control, or in the possession, of the Force if that information is relevant and necessary to the matter before the Commission.” While there are a number of other caveats, the principle of access to privileged information in the cause of a proper investigation of police conduct has been established.

42. One of the factors motivating Parliament to grant the RCMP Commission access to solicitor-client privileged information was explained by the former head of the Commission for Public Complaints Against the RCMP. He pointed out that one of the reasons the Arar inquiry was initiated was the fact that the RCMP oversight body of the day had been unable to obtain key information in support of its mandate. If the oversight body had broad rights of access, as did the public inquiry, that might obviate the need to create ad hoc commissions of inquiry.Note 25

43. It should be noted that in proposing the selective penetration of solicitor-client privilege, we are not suggesting the complete sacrifice of that privilege. The privilege would still be in place vis-à-vis other proceedings. This is where the concept of a limited waiver comes in. A limited waiver means that otherwise privileged information may be used for a particular purpose or proceeding, but is not lost vis-à-vis other parties or fora.Note 26 The doctrine of limited waiver, which is increasingly widely accepted, challenges the traditional, but overstated and outmoded adage that waiver to one necessarily means waiver to all.

44. The creation and scope of a limited waiver of solicitor-client privilege can be defined in three ways. One of these is by statute. A number of statutes require that information must be disclosed for a certain narrow purpose prescribed by the statute. When such information is provided, the statute can explicitly provide that this does not constitute a general waiver of solicitor-client privilege. One example is found in subsection 36(2.2) of the Access to Information Act.Note 27 Under the Act, the head of a government institution may be obliged to disclose to the Information Commissioner a record that contains information subject to solicitor-client privilege. Subsection 36(2.2) states that this disclosure does not constitute a waiver of that privilege. Similarly, the Ontario Legal Aid Services Act, 1998Note 28 can compel the disclosure of privileged information to Legal Aid Ontario. Subsection 89(3) of the Act makes it clear that “Disclosure of privileged information to the Corporation [Legal Aid Ontario] that is required under this Act does not negate or constitute a waiver of privilege.”

45. A limited waiver of solicitor-client privilege may also be established and defined by agreement. Though well protected in law, solicitor-client privilege, at the end of the day, belongs to the client, and the client is free to voluntarily waive privilege and to set terms and limits for doing so.

46. Finally, the circumstances which give rise to the loss of privilege in certain information will themselves generally suggest the scope and limits of that loss. So that, in a scenario where fairness demands that privilege is waived with respect to certain information in one proceeding, that privilege may still hold vis-à-vis other parties in other fora.

47. The MPCC considers that, as with the RCMP Commission, legislated access to solicitor-client privileged information, where necessary for the determination of a complaint, is required to address this issue. The Office of the JAG has generally been disinclined to ever advise in favour of waiving privilege, and as noted, takes the view that only the Minister’s actions may lead to a waiver of privilege. More than that, we often differ over the scope of what information is actually privileged (Crown briefs, mentioned above, is an example). Worse still, the vetting of MP material disclosed to the MPCC pursuant to NDA Part IV is done by staff who are not legally trained, and who tend to redact any references relating to legal counsel. This has resulted in MPCC personnel being involved in numerous discussions and negotiations with CFPM legal advisors to have the redactions revisited and (sometimes) corrected. Indeed, the MPCC had set up a joint working group with the CFPM’s legal advisors on redactions to CFPM disclosure with a view to ironing out such problems. But our success with minimizing and rationalizing redactions to disclosure is largely a function of the outlook of the particular JAG officers advising the CFPM at any given time.

48. The MPCC has made numerous efforts over the years to resolve, or work around, the issue of privilege in a way that respects the importance of privilege, while allowing access for limited purposes in certain cases. The Chairperson has met personally with RAdm Bernatchez, as well as her predecessor, on this issue. In a letter dated June 6, 2018, following up on her meeting with RAdm Bernatchez, the Chairperson raised the issue of MPCC access to solicitor-client privileged information on a limited basis, as well as the need for the MPCC to be able to have access in certain cases to sensitive information by being added to the Canada Evidence Act Schedule. On May 21, 2020, the Chairperson wrote to the JAG and the CFPM on the issue of MPCC access to Crown briefs, and is presently awaiting a response. In order to address their concerns about the complete loss of privilege in MP legal advice, the MPCC has sought to assuage those concerns by sharing the results of our legal research into the doctrine of limited waiver of privilege. The MPCC has also developed, and shared with the CFPM (on July 26, 2019), a template letter for requests for waiver certifying the Chairperson’s belief in the necessity of the privileged information and setting out the applicable terms, limits and safeguards for the secure sharing of the relevant information. We are presently awaiting feedback from the CFPM and have followed up on several occasions with the JAG legal advisor to the CFPM. However, without a basic legislative right of access, we consider that these types of measures can bring only limited relief to the problem.

4) The MPCC proposes that Part IV of the National Defence Act be amended so as provide the MPCC with access to solicitor-client privileged information in cases where it is relevant to a fair disposition of the complaint.

F. Easing Certain Evidentiary Restrictions for Public Interest Hearings

49. In the context of a public interest hearing, the MPCC is authorized by paragraph 250.41(1)(c) of the National Defence Act “to receive and accept any evidence and information that it sees fit, whether admissible in a court of law or not.” Such a relaxation of traditional rules of evidence is typical for administrative tribunals, especially those with an investigative versus adjudicative mandate like the MPCC. The modern focus is on the principles of the reliability and the necessity of evidence, rather than on traditional rules of evidence that can serve to exclude valuable evidence.Note 29

50. In the next subsection of the Act, a number of exceptions to this general principle are enumerated. Subsection 250.41(2) of the National Defence Act prohibits the MPCC from receiving in a hearing the following categories of evidence:

- any evidence or other information that would be inadmissible in a court of law by reason of any any answer given or statement made before a board of inquiry or summary investigation;

- any answer or statement that tends to criminate the witness or subject the witness to any proceeding or penalty and that was in response to a question at a hearing under this Division into another complaint;

- any answer given or statement made before a court of law or tribunal; or

- any answer given or statement made while attempting to resolve a conduct complaint informally under subsection 250.27(1).

51. If the proposal discussed in the previous section (E) were adopted, then paragraph (a) above would need to be modified with respect to solicitor-client privilege. The MPCC has no issue with the restrictions in paragraphs (c) or (e). However, in the MPCC’s view, the bolded restrictions in paragraphs (b) and (d) above are overbroad and unnecessary.

52. The intent of these two provisions is to protect witnesses who have been subject to compelled testimony in other proceedings from having this evidence admitted in an MPCC public interest hearing. However, such a blanket prohibition has the potential to exclude highly relevant information from an MPCC hearing, except through the time-consuming and cumbersome means of calling such witnesses in order to obtain their evidence directly. This is hardly the expeditious and informal type of proceeding envisioned by National Defence Act section 250.14 and paragraph 250.41(1)(c). These prohibitions are overbroad in that they are not confined to a witness’s self-incriminating information. In any event, given that the MPCC’s proceedings are non-penal, non-disciplinary, and indeed non-adjudicative, in nature, it is difficult to see how someone could be truly incriminated in an MPCC proceeding. Moreover, the prohibitions apply equally to uncontested factual background matters and to contested issues. To the extent that they even preclude cross-examination on such earlier evidence, these prohibitions reduce the tools available to assess witness reliability, and thereby impede the MPCC’s ability – and that of the parties to the hearings – to uncover the truth.

53. The provenance and purpose of paragraphs 250.41(2)(b) or (d) are not apparent. Their inflexibility is at odds with the admonition to the MPCC to deal with all matters before it as informally and expeditiously as the circumstances and considerations of fairness permit. In other courts and tribunals, statements made before other adjudicative bodies are admissible, so long as their authenticity can be proved. The weight given to those statements is a separate issue, but it is for the body assessing the out-of-court statement to make that assessment and not have it excluded from consideration altogether. The ability of the MPCC to assess evidence for itself is reflected in paragraph 250.41(c) of the National Defence Act which gives the Commission the power to receive and accept any evidence and information that it sees fit.

54. If the issue is one of the reliability of statements made outside of a Commission hearing, paragraphs 250.41(1)(a) and (b) of the National Defence Act give the MPCC the power to compel a witness to appear before it and give testimony under oath. Such a power can be invoked if there is any question about accepting into evidence prior testimony. Furthermore, section 250.44 of the National Defence Act affords complainants and subjects at a hearing the opportunity to present evidence, cross-examine witnesses, and make representations. These powers can be used if needed to prevent the improper use of statements from prior proceedings.

55. There does not appear to be any parallel to the evidentiary restrictions in paragraphs 250.41(2)(b) or (d) in other federal legislation, including in Part VII of the RCMP Act regarding the RCMP Commission’s authority to receive evidence at its public interest hearings. The equivalent Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act provision to the prohibition on receiving into evidence any statements made before a board of inquiry or summary investigation (paragraph 45.45(8)(b)), is limited to incriminating information. There is no corresponding Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act equivalent whatever to paragraph 250.41(2)(d) of the National Defence Act which forbids the MPCC from taking into evidence any answer given or statement made before a court of law or tribunal.

5) The MPCC proposes that Part IV of the National Defence Act be amended such that the evidentiary restrictions in National Defence Act paragraph 250.41(2)(a) be modified with respect to solicitor-client privilege, and that paragraphs 250.41(2)(b) and (d) be repealed.

G. Addition of the MPCC to Privacy Regulations Schedule II

56. A special challenge confronted by the MPCC flows from the fact that the Canadian Forces Military Police Group is not administratively separate from the broader Canadian Armed Forces/Department of National Defence. One consequence of this is that information and records that are not scanned into the Group’s Security and Military Police Information System (SAMPIS) by members of the Military Police may be beyond the control of the CFPM, because the CFPM does not control the broader Canadian Armed Forces/Department of National Defence information technology and management systems.

57. As a result, the CFPM may be unable to disclose relevant Military Police information to the MPCC, even though it may be stored on workplace computer networks or devices. The broader Canadian Armed Forces/Department of National Defence do not consider themselves bound by the CFPM’s disclosure obligations under Part IV of the National Defence Act. As such, records inevitably contain some amount of personal information and offices in the broader Canadian Armed Forces/Department of National Defence feel bound to resist disclosure to the MPCC in accordance with the Privacy Act. This has led to relevant information not being made available to the MPCC, or at least to significant delays in obtaining such information.

58. For instance this has been an issue in the ongoing Public Interest Investigation in Beamish (MPCC 2016-040). In this case the complainant was able to obtain certain information via a Privacy Act request which was not part of disclosure provided to the MPCC by the CFPM. The reason given for this discrepancy was that some military police members failed to scan relevant emails into their investigation file, rendering them outside the control of the CFPM despite the fact that they were on DND servers.

59. Moreover, it is not difficult to envision other situations where records containing personal information, which is beyond the control of the CFPM, would be relevant to an MPCC investigation. Records relating to a member of the Military Police which are under the control of another part of the Department of National Defence could be relevant. This could even encompass Military Police-related records that are under the control of the CFPM, but the CFPM is reluctant to provide them, such as disciplinary records. Records relating to non-Military Police Canadian Armed Forces members could be highly pertinent to the investigation of interference complaints which often involve non-Military Police members as subjects of the complaint. Records relating to Military Police members or operations may be in the hands of Global Affairs Canada in the case of overseas operations. In domestic operations records may be with the Ministry of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness. In the case of joint policing operations, records may be with the RCMP.

60. In situations where non-Canadian Forces Military Police Group records have been unsuccessfully sought, or where the request has caused significant delay, the MPCC has been advised that access to such material would have been possible if the MPCC had been an investigative body designated for the purposes of paragraph 8(2)(e) of the Privacy Act. Under that paragraph, personal information may be disclosed to an investigative body specified in the regulations, on the written request of the body, for the purpose of enforcing any law of Canada or a province or carrying out a lawful investigation, if the request specifies the purpose and describes the information to be disclosed. The investigative bodies able to receive personal information are set out in Schedule II to the Privacy Regulations.

6) The MPCC proposes that it be added to the list of designated investigative bodies in Schedule II of the Privacy Regulations.

II. MORE FAIR AND EFFICIENT PROCEDURES

A. Introduction

61. In addition to seeking more robust and modern legal authorities for accessing information, the MPCC also sees a number of ways to update the procedures for dealing with complaints so as to render the process for dealing with them more efficient and fair.

B. Authority to Identify and Classify Complaints

1) Overview of the Problem

62. Part IV of the National Defence Act is silent as to when the MP conduct complaints process, including the oversight mandate of the MPCC, has been triggered. Standing to make an interference complaint is limited to Military Police members conducting an investigation or in the supervisory chain of command with respect to the investigation. These are easier to identify and interference complainants are more knowledgeable about the complaints process and how to engage it. As such, the question of complaint classification and identification is largely one that pertains to conduct complaints.

63. A valid conduct complaint is a complaint about the conduct of an MP member in the course of the performance, or purported performance, of his or her “policing duties or functions”. “Policing duties or functions” is defined in section 2 of the Complaints Against the Conduct of Members of the Military Police Regulations (the Regulations). This provision reads as follows:

2. (1) For the purpose of subsection 250.18(1) of the Act, any of the following, if performed by a member of the military police, are policing duties or functions:

- the conduct of an investigation;

- the rendering of assistance to the public;

- the execution of a warrant or another judicial process;

- the handling of evidence;

- the laying of a charge;

- attendance at a judicial proceeding;

- the enforcement of laws;

- responding to a complaint; and

- the arrest or custody of a person.

(2) For greater certainty, a duty or function performed by a member of the military police that relates to administration, training, or military operations that result from established military custom or practice, is not a policing duty or function.

64. Such a definition is needed of course because Military Police are soldiers as well as police. They perform a variety of duties that do not, and ought not, attract the special oversight regime established in Part IV of the National Defence Act for their policing duties.

65. The problem of complaint classification and identification also arises at least in part because the MPCC is not the only portal for MP conduct complaint. Conduct complaints may also be made to: the Judge Advocate General, the CFPM or to any member of the Military Police. If another recipient of a complaint were to determine that it was not a valid conduct or interference complaint, they could choose unilaterally not to forward a copy to the MPCC and not to engage the National Defence Act Part IV process.

66. Indeed, this has happened. There have been times when the CFPM has failed to notify the MPCC of complaints received because the complaint was not initially addressed to one of the authorized complaint recipients per NDA s. 250.21 (this issue is addressed in the next subsection), or because it was (unilaterally) determined not to be related to “policing duties or functions.” Sometimes the MPCC would only find out about such complaints when the complainant sought to request a review under NDA s. 250.31. Obviously, this is problematic for oversight purposes. Complaints that ought reasonably to be subject to MPCC review may not get that opportunity, and the MPCC may be unaware of complaints that should trigger public interest consideration under NDA s. 250.38.

67. While an alternative solution might be to require all conduct complaints to be addressed to the MPCC, such a reform is not advised for a number of reasons.

68. First, it would not provide the required authoritative determination as to whether or not a complaint is a valid conduct complaint. CFPM Professional Standards might still take a different view of a complaint from the MPCC, which would mean that Professional Standards would not conduct its initial review or investigation of the complaint. The result would be, in many cases, that the MPCC would, on review, have to undertake a full investigation of a complaint, rather than simply review the complaint, with the benefit of the Professional Standards investigation, as the legislation intends.

69. Second, it should be recognized that there is, within the military, a cultural norm or tradition against raising concerns with external agencies or institutions. In fact, there is a prohibition on Canadian Armed Forces members making what are called “improper comments”. It is stated in the following terms: “No officer or non-commissioned member shall do or say anything that if seen or heard by any member of the public, might reflect discredit on the Canadian Forces or on any of its members.”Note 30 Canadian Armed Forces members are also ordered not to communicate with other government departments unless authorized to do so.Note 31

70. As such, it is suggested that the current authorized addressees for conduct complaints, as set out in NDA subsection 250.21(1) be preserved.

2) Complaint Classification: Is it about “Policing Duties or Functions” (NDA s. 250.18(1) / Regulations s. 2)?

71. At the present time, while we usually agree with CFPM Professional Standards on the classification of complaint, compared with some previous eras, such fundamental matters should not be left to depend on the personalities of incumbents of positions within the CF MP Group HQ and their legal advisors. Moreover, there are still areas of disagreement as to what constitutes a “policing duty or function”, such as the conduct of CFPM Professional Standards investigations and the responsibility of MP supervisors in investigations. The question of whether or not complaints fall within NDA Part IV is an area of ongoing discussion and disagreement, and the MPCC values the perspective of the CFPM in this area. However, there should be, subject to judicial review, someone in the NDA Part IV process who is charged with making the judgment call as to whether or not a matter is properly an NDA Part IV complaint.

72. From the perspective of preserving the integrity of independent oversight, in the MPCC’s view, it is the only logical candidate for this role. Allowing members of the overseen police service to make such a decision raises at least the perception of a conflict of interest. A number of jurisdictions in Canada have taken steps to avoid this problem. In those jurisdictions where the admissibility of a complaint, or the role of the external oversight body, hinges on how a complaint is characterized, it is uniformly the oversight body to whom this responsibility is assigned.Note 32 The only exception appears to be the Military Police complaints process in Part IV of the National Defence Act.

73. Clearly, for an overseen police service to have the role of deciding which complaints against its members were and were not subject to outside scrutiny is illogical and inappropriate from an oversight perspective. It is a non-starter. The most logical way to avoid concerns about the misidentification, or disputed identification, of National Defence Act Part IV complaints is to have the issue determined by the MPCC, subject to the supervisory jurisdiction of the Federal Court.

74. Having the MPCC involved in classifying and construing complaints at the outset would have other benefits as well. There would less likely be significant differences in the interpretation of a complaint, as between CFPM Professional Standards and the MPCC. This would reduce the number of instances where MP subject members need to be named as subject members at the review stage when CFPM Professional Standards did not consider them subjects in the first instance, which is more fair to such subjects. In fact, this recently occurred in three conduct review cases; namely, MPCC 2016‑037, 2018‑022 and MPCC 2019‑038.

3) Indirectly Received Complaints (NDA s. 250.21)

75. Turning to NDA section 250.21, there is a further complaint identification problem relating to how complaints come to be received by the designated addressees in subsection 250.21(1). In the past, there have been instances where complaints admittedly about MP conduct in the course of “policing duties or functions” have nonetheless been treated as non-NDA Part IV, “internal” complaints, by CFPM Professional Standards: the reason being that the complaints were not received by the subsection 250.21(1) recipient directly from the complainant. In such instances, complainants who were unaware of the NDA Part IV process have addressed complaints to the Minister of National Defence, the Chief of the Defence Staff, or their Member of Parliament.